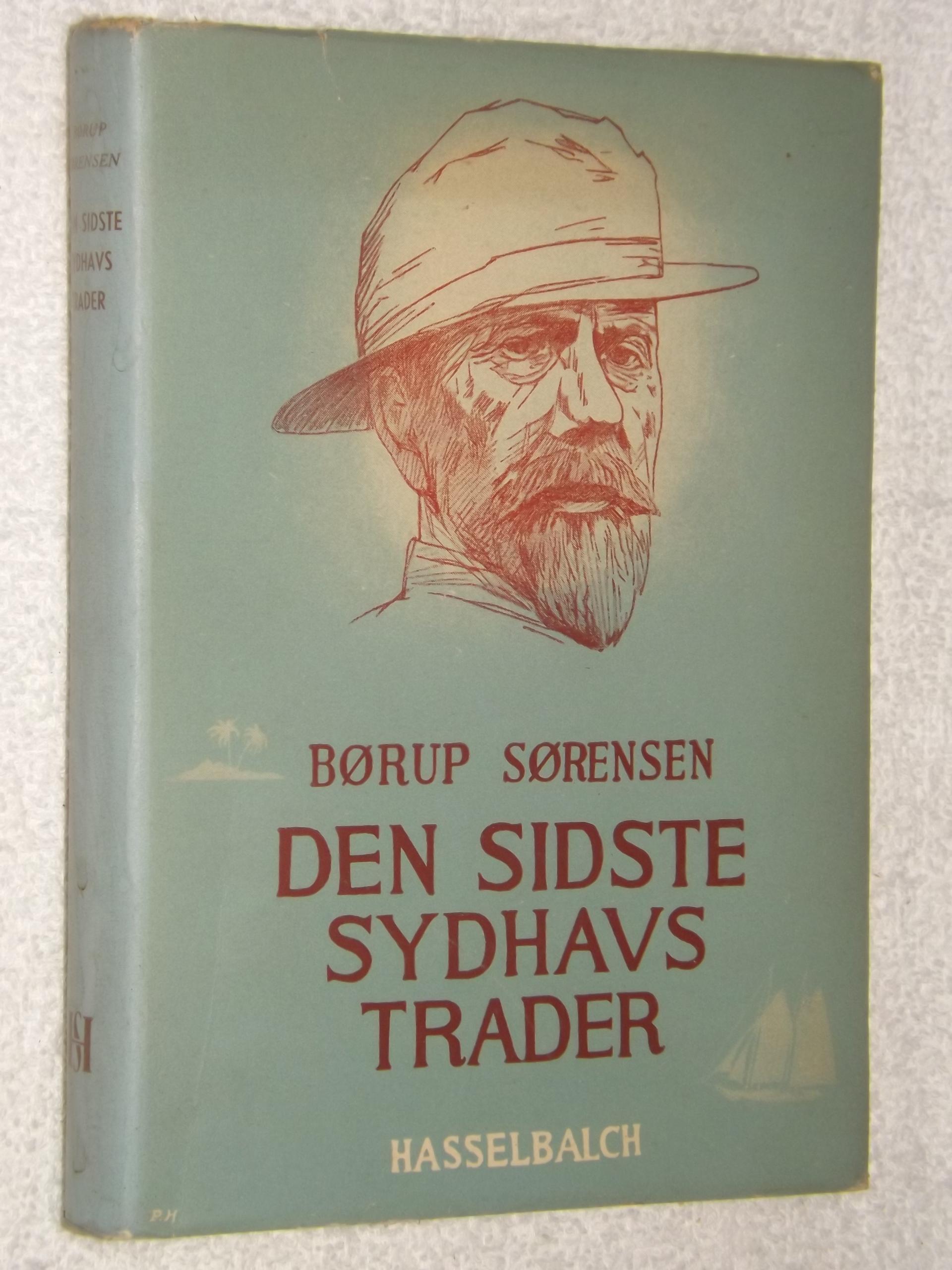

of the last South Sea trader

the Dane German Harry

by Børup Sørensen

Translation by Patrick Lindahl

Chapter 2 - German Harry buys a wreck

Chapter 3 - The ship's boy Sören

Chapter 4 - Harry tries a little of each

Chapter 5 - The first years in the Pacific Islands

Chapter 6 - The women in Harry's life

Chapter 7 - An evening on Ocean Island

Chapter 8 - Ted and the failed recruitment trip

Chapter 9 - Wrecking of "Quetta"

Chapter 10 - The cannon from the Barrier Reef

Chapter 11 - German Harry saves the crew of "Sunbeam"

Chapter 12 - The last days of German Harry

Chapter 13 - The story from Captain Walker

Chapter 14 - The Hibiscus Flower

Chapter 15 - Epilogue

Chapter 16 - Postscript to the Swedish edition

Author's foreword

German Harry is one of the most adventurous figures in Danish sailing history. Ever since Jeppe Sören Christensen, to call him by his real name, ran away from home in Guldager Parish between Esbjerg and Varde in 1863 at the age of thirteen to go to sea, until he closed his eyes for the last time in Sydney in 1914, he experienced so many things as a sailor, smuggler and trader in the South Seas, that his wilde adventures and exploits made him famous all over the world.

German Harry's reputation attracted the attention of many writers. Somerset Maugham wrote of him in his short story in the "Cosmopolitans". The Australian writer Albert F. Ellis tells of him in his book "Adventuring in Coral Seas" and Captain C. A. W. Mockton, at one time Chief of Police at Samarai and in New Guinea, mentions him in "Some Experiences of a New Guinea Magistrate."

Of his own countrymen, I am probably the one who knew him best. For four years I lived with him, accompanied him on a long series of his adventurous journeys, and was with him in his last moments.

On the basis of his own and others' stories, his diaries and notes, I have tried here to give a sober and authoritative portrayal of this extraordinary Danish sailor, the last trader of the South Seas.

Copenhagen, April 1940.

O. M. Børup Sørensen.

Chapter 2

German Harry buys a wreck

Chapter 3

The ship's boy Sören

Heavy snow clouds hung low over the North Sea. The westerly wind, which during the course of the afternoon had changed to a fierce gale, did not bode well for the night, which slowly descended, dark and brooding, over the gray water.

The schooner brig "Emanuel", old and keel-blasted and wide-bowed, made only three knots in the high, white-shimmering sea as she pushed her starboard necks into the wind on her way to North Shields in England.

It was nearly four weeks ago that the ship had left Kristinestad in Finland, where she had been loaded with planks, which in the event of an accident would be good for floating on. It was worse when the schooner was returning from England with coal in the cargo, but that trip probably did not go to the Baltic where there was certainly too much ice at that time.

It was December 22. In two days it was Christmas Eve; then the captain would issue a few bottles of rum to the crew, and if the weather didn't get too bad, they might be able to get to port before the weekend was over. In addition, it would take three weeks to get the schooner unloaded. They could count on staying in England for at least one month.

Captain Clausen, wearing a southwester and an oil coat, dripping with water, came up to the helmsman. He looked at the compass, where the night lamps had just been lit.

"Hold her tight, Peter!" he said to the helmsman, who stood bent over the compass, with a firm grip on the wheel.

"And keep her west-southwest", he continued. "We will surely have a difficult night."

In front of the jib stood the ship's boy Sören, clinging desperately to the halyards. He was the lookout. They were supposed to be close to the Dogger Bank, and it was important to watch out for the fishing fleet. He should have been at the far end of the forecastle but from there he would have been washed overboard long ago, so in a rare moment of kindness the mate had given him permission to stay at the foremast.

Sören was only 18 years old. His full name was Jeppe Sören Christensen and he had seen the light of day for the first time in Todböl in Guldager Parish between Esberg and Varde. He had enlisted as a ship's boy and was consequently next in rank and dignity to the ship's dog Rollo. Rollo had once been a fine, white poodle, but that was a long time ago. He had gradually come to assume an indeterminate dark hue, thanks to the tar with which he had come into contact. But it did not concern Rollo in the least whether he was white or black; he was the skipper's favourite and received the best treatment of all on board.

Sören had run away from his parents' home and gone to sea. He knew that many boys had done it before him, but what he didn't know was that he would never see his parents and his home again.

Only now, as he stood up here on the iced-over deck, holding on to the leeward stay of the foremast, did he realize what he had done. He hadn't said goodbye to anyone back home, he thought and felt a lump in his throat. The brother and the two sisters, would they miss him? And the old well-meaning school teacher, who had so kindly reprimanded him for never doing his homework to which Sören had objected because he didn't need it to keep guard over pigs and geese.

"Very possible, Sören", the schoolteacher had answered, "but there may come a day when you will regret not being more diligent at school."

When the father heard that Sören wanted to go to sea, he became very serious and explained that it was not a life for humans but for dogs. No, Sören would instead become a good farmer and learn to cultivate God's earth. Sören's father used to sing a song to his son about the sailor's hard lot and death at sea, and the only stanzas Sören remembered were the following:

"There is no coffee on the bed,

but maybe it needs to be beaten up first ..."

And that this was true, Sören had found out in the short time he had been on board. He had been seasick, the sailors kicked him along the deck because he could not cope with the unaccustomed work, and every morning he had to get up at 4 o'clock to make coffee for them. Sören wished himself dead many times over. The sailors scratched him when he didn't steal sugar and butter in the galley for them, and the captain, who knew his Pappenheimers, promised to break every bone in his body if he dared to steal anything from the provisions room. But wait, he got big at some point and then ...

"Wake up your drum!" roared the helmsman and a stinging slap in the face roused Sören from his musings. "You call that looking out, huh, boy?"

A large sailing ship, whose mast had gone overboard, drifted past at a distance of a few cable lengths in the darkness. Despite the slap he'd received, Sören couldn't help but look at the wreck with curiosity. What if there was someone on board?

Suddenly, a drawn-out wail was heard from the berth outlet aft. Sören turned in horror and stared through the snow that had begun to fall. After a minute or so, the same plaintive sound was heard again, as if from an injured animal. And now Sören saw in the dim light from the night-house how the captain pulled a crank to a small square box, which stood on the berth outlet. It was the schooner's siren, which had to be started because of the thickness of the snow.

The mainsail had long since been rigged, and now the skipper roared through the storm an order to raise the jib and salvage the mainsail.

"Clear at yards and gig trains, clear at yards and gig trains!" echoed the crew. Soon after, six men ran up the rigging, up into the darkness and the snowstorm, to rig the sails in grand style.

The next morning at dawn the schooner brig "Emanuel" lashed out without a mast before a smoking storm. By midnight the windward bardoons and mitts had sprung and the rigging had gone overboard. The heavy round hulls, which were left hanging from the side of the ship, entangled in the trainwork, had punched a large hole in the bow before the crew could clear the wreckage with the cars. The deck cargo had gone overboard together with the rigging, and the big boat, which had been lashed to the deck cargo, had taken the same route.

Peter, the helmsman, who had turned up on the evening watch, and the helmsman were missing. The rest of the crew, eight men, had lashed themselves to the stump of the mast. The ship was full of water, both the cabin and the gunwale, but fortunately the Finnish planks kept them afloat. For three days the crew persevered, half-dead from the cold and from the water, which incessantly washed over the hull. No-one could untie their lashings to go down and grab something edible. The blades of the pump still held and continued to spin as if to show that all hope was not yet lost. But the leak was too big, and they might as well have stopped the pump.

Sören thought with horror of poor Peter who had gone overboard. Peter was the only one of the sailors who had been decent to him, who had never hit or kicked him. He could, when he closed his eyes, see Peter in front of him, sitting one Sunday morning on the hill when the schooner was still in Kristinestad. With his beautiful voice he sang "Lazarilla's Song", and the Finnish girls threw him kisses. The skipper himself, who at the same time sat smoking his pipe aft, hummed contentedly like an old bear. But now it was all over. Life didn't just consist of singing and Finnish girls; it meant serious and hard work too. His father had probably been right, Sören thought, just as an icy sea washed over the hull and almost drowned them all.

On the morning of the third day the storm abated somewhat and the seas did not so often beat upon them. The captain loosened the rope with which he had lashed himself and with some difficulty made his way down into the cabin where the water reached his waist. He groped his way into the pantry, grabbed a bottle of brandy and a bag of ship's biscuits that were curiously not soaked. Each of the crew received a biscuit and a sip of brandy. However, Sören was so carried away that he could not hold the bottle, so the captain had to put it into his mouth.

At noon the castaways sighted a ship. It was the schooner "Nellie" of Hull. Captain Clausen waved and shouted like a man possessed, but the schooner's crew had already spotted the wreck and steered towards it.

It was a very ill-fated and exhausted crew who next day were put ashore at North Shields, where the consul took them in and procured them lodgings in the seamen's home of the town. "Nellie"'s captain and crew, who had performed the outstanding rescue work, were photographed in the "Illustrated London News" which also published a drawing of Sören with Rollo in his arms.

After a few days, the consul found Sören accommodation in a boarding-house down by the river with a Mrs. Simpson. Mrs. Simpson devoted herself with love and care to the Danish ship's boy, and when the consul, a couple of weeks later after the worst horror had passed, asked Sören whether he wanted to go to sea again or be sent home, Sören unhesitantly chose the sea. This pleased the consul a lot as it saved him the money for the boy's journey home.

On board "Fortuna", Sören developed into a first-class sailor. After a couple of years, he was the best when it came to rigging sails, splitting rigging and standing at the helm. He soon learned to speak English like a native, for no other language was spoken on the barque.

Sören made many wonderful trips through the blue Mediterranean and learned to love the sea with a love that never left him. Like all true sailors, he forgot storms and hardships as soon as he had been in port for a day.

However, he did not forget Mrs. Simpson, who had been like a mother to him when he first went ashore in North Shields. Every time Sören came to England, he stayed with here until he set out on his travels again.

One beautiful evening a few years later at the beginning of May, the "Fortuna" was in the dock, ready to go to sea. The pilots had come aboard, and friends and acquaintances gathered on the wharf to bid farewell. Among the farewellers were also seen Mrs. Simpson and her 16-year-old daughter Nancy, a sweet and pleasant girl, who seemed to have an eye for the young Danish sailor who sang with his young strong voice the song about "Rio Grande" while the comrades stomped on the walking game and from time to time joined in the chorus:

"Way Rio, Rolling Rio,

Sing fare ye well,

To my pretty young girl,

we are bound for Rio Grand!"

It was not easy for Nancy to say goodbye to Sören, and she constantly wiped her eyes with her handkerchief. So much could happen on such a long journey. Sören waved a last greeting to Mrs. Simpson and Nancy, then he pulled his cap down over his eyes to hide his emotions and busied himself with sails and hawsers. "Such a wonderful girl", he thought and stroked his eyes with the back of his hand.

Five years later, Sören signed off from the barque "Fortuna" and said goodbye to the sea. He had acquired a taste for the comforts of home and, after a while, married Nancy. And suddenly, when Mrs. Simpson passed away, he found himself to be the owner of her boarding-house and a good English citizen into the bargain.

This episode of Sören's life is somewhat shrouded in mystery. It is said in some quarters that he engaged in "shanghaiing" sailors, and there are wonderful stories about his activities. Personally, however, I have never believed these rumours, mainly because there were no people to be "shanghaied" in the English coastal towns, least of all for the merchant fleet and not at all at the time when Sören Christensen was staying there. In England there was really only one kind of "shanghaiing" being done and that was by the Royal Navy which had the legal exclusive right to "shanghai" people as crews for the the men-of-war through so- called "pressers" who combed the ports' inns and taverns and violently dragged sailors aboard.

However, it is proven that Sören was involved in smuggling. His specialty was opium, and much of this Eastern drug is said to have found its way through Sören's boarding-house to London's Chinatown. But that's no reason to disapprove of Sören's character and morals; it has to be remembered that those were different times then, especially among sailors.

Business went well and money flowed in, but Sören eventually found out that he was not meant to be a landlubber. When he was at sea, he longed for port, but when he had been on land for a time, his old longing for the sea began to re-awaken. So one fine day, after various controversies with Nancy, when Sören, like so many others, realised that first love does not last forever, and the English authorities wanted to talk to him about a failed smuggling story, Sören decided to disappear. With only 10 pounds in his pocket, he re-surfaced in Hamburg at the end of 1874.

There he started his rollercoaster life in the streets of St. Pauli. It wasn't long before people started to respect his huge fists, and the funniest part was that he knew how to clean houses. When he reached a certain stage in a happy team with good friends, he used to get up and say with an adult voice: "Yes, now we clean house here!" What happened next could rarely be explained clearly afterwards, but Sören did not give up until everyone in the place, including the host, was out in the yard or the street. Then it might occur to him to make up for the pleasure on the spot and offer drinks over the top. It could hardly be avoided that he occasionally sat around and one day, when he thought it might be useful for a little change of climate, he enlisted as a sailor on one of Rickmer's large sailing ships, the "Nathalia Rickmers", destined around Cape Horn to Chile to pick up saltpeter. He enlisted under the name Harry, a name that from that moment came to follow him for the rest of his life.

On board the "Nathalia Rickmers", Harry, as we will henceforth call him, learnt what it meant to be a Cape Horn sailor. The nitrate ships in the saltpeter trade were worthy successors to the old tea clippers with their record-breaking voyages. If a captain had made a record-breaking voyage, he was praised at home and held up as an example to his peers by the shipping company, until some competitor beat his record by another day or two. Then the former recordholder was called to the shipowner who gave him a warning and urged to better his times or else look for another job. The consequence of this system was, of course, that the captains were forced to take unreasonable risks, which affected both ships and crew. Eventually there wasn't a German left who wanted to work on those notorious ships, so that eventually the crews were made up of Scandinavians, Finns, Italians, Greeks, and even Negroes. On board "Nathalia Rickmers" a Babylonian bewilderment reigned with at least ten languages. It was also said that when the captain turned in for the night, padlocks were put on the spars and halyards so that the helmsmen would not be tempted to lower the sails. A trip where only one or a couple of men went overboard and drowned was considered normal.

The cook on board the "Nathalia Rickmers" was a Chinese and according to the muster roll, his name was Ah Mour. He was a real starving artist, it was said, and with the help of a few bones, water and an octopus could conjure up a delicious dinner. But when the ship had been at sea for a couple of months, a cooking expert was also needed to be able to produce something edible from what was in the provisions: rancid salt meat and pork and dry ship's biscuits, as hard as flint, from which the worms had to be pounded out.

Ah Mour had a face like a sphinx, and even if the ship were to be wrecked with all men lost, not a muscle would have moved on his unscrutable face. After the ship sailed from Hamburg, he did not utter a word to any person on board. The first time he opened his mouth was when one of the crew had appropriated a couple of roast chickens, intended for the captain's table. He muttered just a few words to the captain:

"Man steal chickens!"

The captain was furious. "Fischer", he said to the first mate, "call all men aft."

The crew assembled on the aft half-deck, where the captain stood next to the helmsman.

"With sadness and resentment I have been forced to state that my crew is stealing", he began. "I urge the guilty one to come forward and receive his well-deserved punishment."

The sailors squirmed and peered from under their lowered heads at each other, but none pleaded guilty. After a while the captain broke the deep silence and growled, "From today you get half-rations until the culprit reports. I will indeed" - he swore a rough oath - "teach you!"

For three days the crew survived on half-rations. Already, portions were usually small, but half-rations were pure starvation. After three days, Harry went aft to the captain to confess that he was the thief. The captain understood very well that he was lying, but heaved a sigh of relief and whispered: "It must be that there is a fellow-thief out there on the schooner!" From this moment, because he got them full rations again, Harry became very popular with the crew. .

The second mate's name was Schultz and he was from Bavaria. You couldn't find a more unpleasant person. He used to chase the sailors around the deck like dogs and beat them in the skull with a heavy belaying pin. In fact, he was afraid of the men, who hated him dearly. The captain didn't like Schultz either, but used him to make the crew work harder.

The "Nathalia" behaved like a hysterical woman. She rolled heavily in the sea, with the mastheads often swinging twenty metres to either side. A desperate attempt was made to round Cape Horn when the wind was favourable for once. The course was straight west. On the starboard side, but out of sight, you had the storm-whipped rocky coast of Tierra del Fuego, the Land of Fire, the most God-forsaken region on earth, and on the port side you could now and then between the torn the skies see both the moon and the setting sun cast a rare shimmer over the vast seas where the Atlantic and Pacific meet.

The captain was furious because it took an hour to fix the mainsail. Harry, along with ten other sailors, lay on the heavy iron bar on the starboard ridge, struggling with the thick canvas, which felt like icy wood to handle.

Glancing down to the deck, Harry saw Schultz chasing a Finnish sailor, who always walked around with a terrified expression on his face, onto the splitter boom to secure the splitter. When the entire forward ship was periodically dipped into the high sea, everyone could understand how it would end for the Finn. Just when they had finished the square topsail, a huge wave came and buried the whole hull; the Finn, who was out on the yardarm, could not hold on and was swept into the water. Harry shouted, "Man overboard!", but Schultz yelled at him to shut up. There was no way to put a boat out in this weather, and that idiot didn't have to sleep outside on the bowsprit! The crew stared after their comrade and grumbled. After a while they caught sight of a pair of large albatrosses circling over the spot where the Fin had disappeared. The albatrosses only peck out the eyes when they get hold of a drowning sailor, Harry told me.

With rapid speed the ship rounded Cape Horn and was soon in tropical waters again. The freight consisted of general cargo for China and Japan, and on the return journey they would stop on the west coast of South America to load saltpeter. A fortnight before arriving at San Francisco, a couple of large rolls of bream sailcloth disappeared from the storeroom, and could not be found despite a thorough search. It was the sailors’ intention to make tents from the canvas for the gold fields of the Sacramento Valley, when they fled to San Francisco. On the way home around Cape Horn, mate Schultz also disappeared on a dark and stormy night in roughly the same place where the Finn had drowned. The captain briefly interrogated the crew, but to no avail, and no-one cared about what had happened.

Harry made two trips on the "Nathalia Rickmers" and then signed off in Hamburg. He then sailed with a Norwegian barque to Brazil and the La Plata, and then once again joined the saltpeter trade on one of the famous P-Line barques from Hamburg. For two years he sailed with this line and became the best sailmaker on the route, much sought-after by the captains.

One night, when the ship was in Oakland unloading lumber, Harry escaped. He went ashore together with a Norwegian sailor named Andersson who had no money. "It doesn't matter", Harry comforted him. "When I have money, you have money too. I pay."

They entered land on a long wooden bridge just as a large American flat-topped schooner slipped through the Golden Gate. Harry pointed towards the ship to explain the sails to the Norwegian, but got no answer. When he turned his head to look for his companion, he was gone. Harry couldn't believe his eyes, because there wasn't a cone on the entire bridge. After a while he heard desperate cries and saw Andersson, who was lying in the black water under the bridge and clinging to the slippery bridge pillars. He had simply fallen through a hole in the bridge.

Harry got hold of a boat and got his mate back onto dry land. A couple of glasses of cognac at the nearest bar worked wonders. And while Harry and Andersson were sitting there at the bar, the rest of the crew from their ship eventually arrived. The whole pile had escaped to go up to the gold fields at Sacramento. The temptation was too great and several ships lay in the harbor without crews. Yes, there were ships where the officers, even the captain, had run away to try their luck. It was at that time that the famous sailor's song "Sacramento" came into being. The refrain was:

"Blow boys, blow,

for California!

There is plenty of gold,

So I've been told,

on the banks of Sacramento".

On the "Barbary Coast" in San Francisco, Harry amused himself to his heart's content for three weeks, reliving the wild adventures of his younger days in Hamburg. Then he disappeared up to the gold fields to try his luck for a while, but to no avail. One evening he was ambushed by two armed bandits, but was lucky enough to survive one and nearly choked the fellow. The other took to the harrow. Harry then left the goldfields, signed on with an American schooner in San Francisco, and disembarked a month later in Callao, Peru.

Chapter 4

Harry tries a little of each

Chapter 5

The first years in the Pacific Islands

Coming from the west coast of South America with its dry, unhealthy climate to the mild South Sea islands must have been like coming from hell to heaven for Harry. Here was everything a human being and an adventurer could wish for. Wonderful palm islands with verdant vegetation and sparkling white sandy beaches and fruits that you only had to reach out for. It is hardly surprising that the white-haired sailor settled here in this earthly paradise and remained there for the rest of his life, with the exception of a short visit to England later on. Here he also got the name, which later became famous far and wide. At the same time, an English sailor, also named Harry, appeared in Cooktown; he was called Welsh Harry while our Harry, who was so well versed in the German language, was christened German Harry.

German Harry was broke when he came to Cooktown, and with his ravenous appetite for life he took every chance that came his way. He was not afraid to cut in if it was necessary, but it goes without saying that his upbringing in life's own hard school meant that he was not so accurate with the bourgeois laws. Smuggling was a business he knew, and here were all the opportunities that, according to the proverb, make a thief. He boarded the China boats, which arrived every week, bought silks, gems, and opium, concealed the contraband in pigs' bladders, filled with air, and let them go overboard through some ship's valve, whereupon he could fish out his goods. He felt wind and current conditions on his five fingers. 59

Customs had a good eye for him, again and again he was thoroughly examined when he went ashore but of course without the slightest result. Nor did it succeed for the zealous customs snoopers to discover his methods.

However, all this was, as far as Harry was concerned, only small things and a small beginning of what was to come. He had other and bigger plans. But this required capital, and Harry kept a watchful eye on every opportunity to obtain such. The first chance presented itself as follows:

After the discovery of Hodgekinson's goldfields, the Government wished to establish a port nearer to them than Cooktown, and offered a reward of £200 to whoever could point out a suitable place where a port could be built and a road made over the mountains to the goldfields. At that time there were no railways in Queensland.

Harry thought it was best to search from the sea side. He bought a boat, had it rigged with mast and sails, hired a helper and set off. Another man named Bill Smith and a negro, who knew local conditions, had set out on the same errand and had eight days' lead. As soon as Harry found a place, which he thought was suitable for the purpose, he went ashore, pitched his tent, and began to build a hut. The next day he continued in his boat up a small river to find, if possible, an even better place. Here he met Bill Smith and the Negro. They too had marked out a place which they found suitable and moreover they had already been up to the gold fields and brought back a couple of the gold diggers, in order to prove with their help their pre-emptive right to the reward.

The government took the two proposals under consideration and found the place where Harry landed best suited for the port building. In the same place is now the city of Cairns. Where Harry built his hut, the main street now stretches out and where he put down his tent stakes rises a building housing the town's bank. But Bill Smith, much to Harry's chagrin, got both the £200 reward and all the credit, because he had been first up to the goldfields.

Harry didn't lose heart over that, though. He consoled himself with his favorite proverb: "No night so dark that there is no bright day afterwards!" and decided to find some other ways out. He stayed for a couple of years in Cooktown and made good money serving as a gold carrier over the mountains, but then roads were built, gold transport was arranged differently and Harry turned to the sea again. He started fishing for trepang, a kind of "sausage", which the French call "bêche de mer" and which is a favorite dish of the Chinese. These anchovies live on coral reefs and are fished with an iron hook on a long shaft. The red trepange is particularly valuable and brought in at that time up to 4000 shillings per ton. Harry bought a schooner which he named "Captain Cook", hired about forty Chinese and began fishing on the Great Barrier Reef, which stretches along the coast of Queensland from Brisbane to Torres Strait in the north between New Guinea and Cape York. The fishing was extraordinarily profitable, the Chinese wading on the reef with their iron hooks and a bag on their bellies and making good catches. On Rheine Island the trepange was treated according to all the rules of the art and Harry rushed provisions and water there from Cooktown. In doing so he used the same channel through the reef as Captain Bligh on his famous rowing trip after the world-famous mutiny on the "Bounty".

Rheine Island was a deserted bank without the slightest trace of vegetation. Nowadays there is a lighthouse, but when Harry stayed there it was as desolate and lonely as when Bligh found it a hundred years before. From Rheine Island, Harry shipped the finished trepange back to the mainland and made some rough money. In addition, he sailed between the islands with dynamite, intended for the gold mines.

As an example of how thoroughly Harry went about it, one day he bought the New Zealand brig "Maggie" stranded at the mouth of the Daintree River. He had actually bought the wreck for scrap, but before this happened he lived on board the schooner for four months and used the time to study navigation, as all the necessary instruments, books and charts remained on board. It had always been in his head that he couldn't navigate on his own and here he now had the opportunity to learn everything he would need. The roving life had created a gap in his knowledge, and he had often had reason to ponder the admonishing words of the old Jutland schoolmaster that perhaps a day would come when he would find use for bookish knowledge. And when he sat alone in the cabin struggling with numbers and nautical calculations, he bitterly regretted being so lazy at school.

Harry had already intended to buy a bigger ship, on which he could smoke the sausages on board and on the whole set up more practically and spaciously, when one day he was shipwrecked with "Captain Cook". He was leaving Rheine Island one fine morning on the usual trip to Cooktown with his load of trepang, when about a couple of nautical miles from the island he was surprised by a violent squall. His crew, a couple of Chinese and a Danish boy who had enlisted at Cardwell, were sitting between the open hatches on the deck, eating breakfast in good company, when the schooner capsized, filled with water, and sank within a couple of minutes. Harry was the only one who escaped from the adventure alive. He was just about to drown, when he saw a floating hatch and climbed onto it. And afterwards he could swear that, as he lay on the hatch and paddled forward with his arms and legs, he could see Captain Petersson, a Swede who was foreman for the Chinese, standing on the island and watching his struggle for life through the binoculars without doing the least to help. Petersson was already in the process of taking over the lead of the trepan fishing when Harry suddenly, after four hours of violent effort, crawled onto the beach bed, panting like a hippopotamus. However, he didn't give himself time to rest or dry off before giving Petersson a real beating.

After this mishap, Harry travelled to Brisbane and bought a beautiful schooner, which the government offered for sale. He intended to continue with the fishery, but the Chinese had other plans. They went on strike that they were not employed in fishing with the schooner "Lizzie," as the new schooner was called, but with the "Captain Cook." Behind the whole story was a clever manager, who saw a good deal in the money-rich Harry and therefore had caused the Chinese to strike. However, Harry didn't think it was worth sacrificing any money on possibly long-lasting processes, but shut down the trepang fishing and sent the Chinese home so that the careful manager had to look after the estimated profit.

It wasn't long before another chance appeared. Just then, large gold fields had been discovered at St. Aignan, Sud-Est and other islands off the coast of New Guinea and on New Guinea itself. Gold diggers flocked in by the thousands, and Harry determinedly started regular passenger services between the mainland and the islands. Every time Harry came to Cooktown there were crowds of people on the docks waiting For "Lizzie". Everyone wanted to go with Harry, because he had the reputation of being the most skilled navigator between the islands. When sailing through narrow passages in the coral reefs, he always stood up at the donkey's head on the foremast and waved to the helmsman whether he should keep starboard or port. From there he could see down into the clear water and direct the course in time. Yes, there were even people who claimed Harry could "smell" his way to hidden shards, reefs and underwater rocks. The competition was great, other skippers also led the way, but although even the great Burns Philp Line fielded two steamers, Harry maintained his leading position, and if a steamer out-competed him on one route, he immediately recovered the damage on another. At one time he had no less than six schooners in operation, but always himself in command of the flagship "Lizzie." He constantly bought and sold ships, and one day, when he had only the "Lizzie" left, he went to Sydney and returned with a whole flotilla, consisting of twelve schooners. It left the other skipper along the coast speechless.

With this sizable fleet at his disposal, completely different possibilities opened up for Harry than just passenger traffic with gold diggers. He had several pearling stations in the Gulf of Carpentaria and in the Torres Strait. His ships were always manned by coloured men, namely Australasian negroes and Malays. The coloureds were honest, he said, while the whites were not to be trusted, and if a ship went down it was just so many niggers who had drowned, if it was whites, the whole thing became more complicated. Besides, most of the whites had a fault, namely that they drank themselves silly, a course of action which Harry, who himself never tasted a drop on board, strongly condemned. Just a single time

Harry tried using white. He modelled an old English sea bear called Old Jack and a white chef.

The latter proved to be on the verge of delirium tremens and had to be put ashore after two days, and Old Jack, who had been with the fleet once upon a time, was no better. The only thing he was good at was standing at the helm when the schooner was in port, and that wasn't much fun.

During the time Harry was fishing for trevally on the Barrier Reef, something happened that is perhaps worth mentioning, not least because it gives a good picture of the conditions at the time and explains why Harry could sometimes appear more heavy-handed than a modern person likes and understands .

After the shipwreck with "Captain Cook", Harry dismissed the Swede Petersson and hired an overseer named Mac Gregor. He was a Scotsman and was mostly interested in whiskey and a comfortable existence. He had another white man as his assistant, and the rest of the "staff" consisted of 10 Chinese, 5 Malays, and 4 natives from one of York Peninsula's wildest tribes, which most whites otherwise used to get out of their way.

One day Harry had sailed to Cooktown with a load of trepang and came back to the station on Rheine Island to take on new cargo again. He had been gone for a week. When he went ashore at the wharf he found it deserted and abandoned. Not a human was seen. In the warehouses there was a lot of trepang, ready to be shipped, but the smoking ovens were cold and abandoned.

Harry walked across an open space where the catch was being dried in the sun and towards the workers' dormitory, a large barrack with a corrugated iron roof. As he looked into the half-dark room, a terrible stench hit him. However, he went in and found all his people, including the Scots and the white assistant, lie murdered there. Their heads had been smashed with an ax lying in a corner of the shed.

It didn't take Harry long to figure out how it all worked out. The fact that the four natives were missing gave him sufficient certainty. Nor did he hesitate for a moment as to where he would find them.

At night Harry and the two sailors he had brought with him to Cooktown caught a pair of giant turtles and the next morning they carried them aboard the schooner and sailed over to the mainland. From the coast they headed inland. The two sailors carried the turtles between them, Harry going last, armed with a Winchester rifle with 14 rounds in the magazine.

Twenty hours later they reached the native tribe, whose camp site Harry knew beforehand. And here he found the four escapees and about thirty others engaged in various games and weapons exercises. Harry pretended he came as a friend. He noticed the four of them looking at him uncertainly from under their bowed heads, but he didn't pretend not to notice and handed over the two large turtles as gift.

Harry and his two men sat at a distance and watched the blacks as they oiled the gizzard. But suddenly a couple of them started doing high crunches and rolling on the ground. At the same time, Harry opened fire with his winchester. Some blacks tried to escape, but they didn't get far. The turtles were prepared with a fast-acting, deadly poison. Not one of the tribe escaped with their lives. Harry's revenge was complete.

On the return trip, Harry rescued two Australasian negroes who were floating on a tree trunk far out to sea. The two men were half dead of hunger and thirst, but Harry nursed them back to health and then made a long detour to land them on the shore. That was German Harry!

The next time Harry came to Cooktown he reported to the authorities the murder of MacGregor and the other white. His private revenge, on the other hand, he didn't mention.

One day on the way home from Cooktown, Harry, who was on the lookout for reefs and seabeds, spotted four men on a low sandbar. He maneuvered his schooner as close to the bank as possible, had a boat put into the sea, and took the four castaways on board. They told us that they belonged to a party of twenty gold diggers, who had been returning from New Guinea on board the schooner "Saucy Jack." The ship had run aground on a rock.

"Where is that rock and how many were on board?" Harry asked.

The four rescued explained that they had taken the boat to row for help and that the other sixteen were probably still on board the "Saucy Jack". However, they had rowed around for so long that they did not know where the stranding had taken place. A couple said it was in a westerly direction, others that it was in the east and Harry was at a loss for words.

Despite being short on provisions and water, he vowed to save the castaways, no matter the cost. It was impossible to steer between all the dangerous reefs, shoals and sandbanks, so Harry sailed up to a small island on the Barrier Reef, anchored there and put a boat into the sea. For three days he cruised with a couple of men on board between islands, reefs and rocks to find "Saucy Jack", but without success. When he was back on board the schooner, one of the four castaways remembered that he had noticed a strangely shaped rock when they stranded. From the description, Harry thought he knew where it was and gave the order to drop anchor. He set course for the north, and four days later he actually succeeded in finding the wreck of the "Saucy Jack" on a coral reef and rescuing the sixteen gold diggers. It was at the last second because they could not survive many more hours without food and water.

In fact, it was a remarkable feat for Harry to find the stranded ship in the then only partially charted sea of thousands of islands, rocks and underwater reefs. The rocks where the gold diggers' schooner had run aground, Harry named after "Saucy Jack" and they are still called that today.

A month later Harry was passing through the Torres Strait into the Gulf of Carpentaria, which is 300 nautical miles wide and filled with islands, inhabited at that time by natives who had never seen a white man. Harry was looking for new pearl banks and visited islands such as the Wellesley Group, Sir Edward Pellew Group, Groote Eylandt and many others and finally reached Cape Wessel, from where he could look out over the Arafura Sea.

At Rocky Island, where he went in to fill up with fresh water, he had an incident that could have ended badly.

As Harry took on water, the natives streamed down to the beach to view the ship. The men were completely naked, their only "clothing" consisted of a few bone and stone wedges in their noses and ears. The women, on the other hand, were "dressed" in a finely braided bast band, which was wrapped a few times around the waist. They were magnificently built and

Harry immediately liked them. He lured the most beautiful one on board, and she apparently helped escape with the white chief. But then Harry and his people would rowing out to the schooner, the natives held the boat's catch line so that they could not get out into deep water, and at the same time a shower of javelins and arrows rained down upon them. The beauty, who apparently believed that sooner or later Harry would end up in the pots, took her part, jumped overboard and went ashore. But she had scarcely reached the beach before she was knocked to the ground by a great burly fellow with a huge club in his hand, and Harry had so much feeling for his chosen one that with a well-aimed shot he sent her brutish tribesman to the rare hunting grounds. A spear, which one of the crewmen instantly seized in flight, might easily have dispatched Harry in the same manner.

After a fierce battle, however, Harry and his men managed to break free from the beach and in a moment the schooner weighed anchor.

In the Gulf of Carpentaria, Harry found several fine pearl shoals and marked the find sites by anchoring small cork buoys with flags next to them to return later with Malay divers and necessary pearl fishing equipment.

In most places along the coast the natives fled when they saw Harry's ship, but on the islands it was better when he traded his provisions in the form of fruit and water for common trade items such as knives, cheap pocket mirrors and other knick-knacks.

Harry reached Cape False on Frederick Henry Island, then sailed east and one day stopped at the small trading station of Sukarie on the coast of Dutch New Guinea. As he rounded the headland at the entrance, he noticed a white merchant schooner at anchor, but decided to wait to visit it until the next day.

Late at night, Harry sat in a deck chair on the deck, refreshing himself with a cup of tea, like one of his native crewmen made ready. The night was still and the sea lay like a mirror. Inland, he could see the dark forests rising behind the coconut palms by the shore, and even further away, forested mountains rose against the deep blue night sky. The moonlight played across the roof of the administration building on the outskirts of the small town.

Suddenly Harry heard a splash in the water at the side of the ship. He stood up and saw a white man who was just climbing out of the water.

"I was lucky to meet you, Harry", the man said as Harry, with a strong grip on his neck, dragged him aboard. "The accursed Dutchmen are stealing the schooner from me and tormenting the life out of me!"

"Now let me hear of your troubles", said Harry, who at once recognized in the wet form one of his old friends, Captain Hamilton of Sydney. "Why you come swimming here like another nigger in the middle of the night?"

Hamilton told: He had run into the harbor with his schooner "Daisy" but had been fined fifty pounds because he had no clearance papers from the previous port. Unable to pay, the authorities seized the schooner and refused to release it until the fine was paid. Hamilton was in fact under arrest but the authorities did not bother to lock him up. He was careful enough, they thought, not to escape into the mountains and be eaten by cannibals, and besides, they had the schooner as pawn. Now he had gone a whole month and starved ashore.

"To imagine being arrested by that pack of thieves in this godforsaken den!" Hamilton said, spitting out a mouthful of water over the rail.

"I notice the blessing of civilization has come to this town as well", Harry said, opening his safe to examine his current financial resources.

"Here's £45 and the rest in Chilean dollars, that's all I have for the moment. Arrange for you to pay the bloodsuckers and get away. And then you'll have to forgive me for also disappearing, I don't have any papers either!"

An hour later Harry was far out at sea. Among other things, German Harry owned two large schooners, "Galathea" and "Hygyea", which were leased to the Phosphate Guano company. These two vessels sailed non-stop with cargoes of guano from Reine Island to Melbourne.

At some point, Mr. Arundel, the director of the company, went to Reine Island and from there to Thursday Island and thus got to know Harry. He then never got tired of telling his acquaintances about Harry's exploits.

When they were at Thursday Island, one of Harry's curly-haired Santa Cruz boys ran amok. Harry stood in the bow scouting for a good anchorage, when the black man approached him from behind, axe raised, ready to send him to eternity. At the same moment, Mr. Arundel rose from the cabin and shouted at the top of his lungs to Harry, who turned in a flash and glared at the black man. He dropped the axe in shame and lurched aft. Then he suddenly jumped overboard and swam towards shore.

Not a muscle moved in Harry's face as he took the winchester rifle and cocked it. "Yes, he really deserves to die, that assassin!" said Mr. Arundel.

Harry didn't answer. He took careful aim and a shot was heard. The negro splashed around in the water and to his great surprise Mr. Arundel watch him swim back to the ship and climb back on board. He fell to his knees in front of Harry, clinging to his legs and whimpering like a whipped dog. Harry told him to go ahead and do his work.

Later in the day, as they sat at the table, Mr. Arundel Harry: "Why didn't you shoot the black beast?"

"Shoot?" Harry replied, "I didn't have the remotest thought of shooting him."

"But I saw with my own eyes that you aimed at the man's head and missed. And why did he come back, they don't usually do that. I don't understand a bit of it all!"

Harry smiled. "I didn't miss him. On the contrary, it was a real hit. A shark at least fourteen feet, about to sink its teeth into the weakling. It got the bullet right between the eyes and it went to the bottom like a stone."

He looked thoughtfully at his glass and continued: "The Santa Cruz man is one of my best men. And he will henceforth be faithful as a dog."

Such was Harry's attitude towards the natives who came into his service. He himself recruited the workers for the pearl fisheries from the small unknown islands of the Pacific Ocean, from the river areas of New Guinea and the most uncivilized regions of the York Peninsula. He understood how to treat the natives the right way and never showed any fear, even though his life often hung in the balance. This created a mutual respect, and the natives looked up to him as a god. He never once broke agreements made and was one of the few traders who never had a native abducted against his will. He also procured workers for the rubber and coconut plantations in New Guinea and for the sugar plantations in Queensland, and when the terms of the contracts expired, he sailed them back to their respective home islands.

Harry's business soon grew beyond all limits. He also engaged in illegal pearl trading, that is, he bought pearls from divers who were employed by other pearl fishermen. These divers were always eager to sell to Harry. Harry's black Austral negroes, which he used on some pearl banks, could not dive in deep water, and he was therefore unable, with the help of his blacks, to procure the large quantities of pearls which he occasionally brought with him to Sydney.

Harry also bought large tracts of land from the native chiefs of New Guinea and acquired entire islands off the coast, where he planted palm trees and established plantations, including rubber plantations. He had his hands full and was well on his way to becoming a real man of substance. He was the most famous and talked about ship owner and plantation owner in this part of the globe and people counted him as a man of great importance. His bank account in Sydney grew slowly but surely.

But one day a stick stuck in the wheel. Civilization was advancing. Germany and England annexed New Guinea but did not want to recognize Harry as the rightful owner of the lands and islands he had acquired. Harry raged like a berry and invoked his ownership, but to no !--- raged like a berry ---> avail. He was treated as a pirate and adventurer, and he sacrificed thousands of pounds in vain on lawsuits and lawyers.

Governments are nothing more than a band of legalized robbers, Harry thought.

Otherwise, you would think that with all his many businesses, Harry should have amassed fabulous riches. That was, Bell". As they approached the door of the hotel bar, there was shouting and noise from within, and at the same moment a negro rushed out with his stomach distended. A Greek gold-digger had stabbed him with his knife. It is perhaps needless to say that Harry was not allowed to sell some hotel that night.

One day Harry met a man who didn't really like him. It was Sam Griffith. Sam, who was then Premier of the State of Queensland, had set his mind on organizing the whole motley collection of immigrants who lived in these areas, and above all he wanted to put an end to the abuse of the natives. It is true that there were strict laws against kidnapping and slavery and definite regulations for the work of the natives on the sugar plantations, but regardless, traders and schooner captains employed formal pat-hunting of them and treated them like animals. Sam Griffith made it his life's aim to remedy these wrongs, and therefore he did everything to instill the fear of God and Sir Sam into the hardened hearts of the depraved. Many were beaten with irons, others were hanged, and the South Sea traders realized that the good old days were over, that their kingdom was tottering in its foundations.

German Harry, who with all due respect to his good sides was no angel, found himself having several unsolved dealings with the law and order and therefore thought it would not hurt to have a little climate change. He sold his ships to the firm of Burns Philp, who also took over his plantations and other properties, and with his pocket full of good pounds he boarded a ship and sailed as a passenger to England.

Chapter 6

The women in Harry's life

Chapter 7

An evening on Ocean Island

One evening the three merchant ships Ellison, Danty Louis and Smith had come to anchor with their schooners at Ocean Island. They were now sitting talking over a grog on land. Out in the lagoon, the schooners were reflected in the shiny water, a cable's length from the beach bed. To the south, the huts of the natives and the small town of Taipang loomed between the tall coconut palms.

It would be fun to know if German Harry is going to run in here if he comes by, Ellison said during the conversation.

Why would he come here to Ocean Island? asked Danty Louis. The Burns Philp boat which I passed yesterday had seen German Harry's "Lizzie" on a southerly course, probably bound for Sydney from Hunter Island with clam shells, copra or God knows what cargo he has this time. He always has a full load when others can't even get it together for ballast. And we hope he pops in here, if he comes by, right Smith? Ellison's last remark had a definite undertone. Smith, who was a pearl buyer, owed Harry £50 and, incidentally, was not exactly counted among the Great Dane's most intimate friends. He has no papers as a captain, said Smith sullenly, it would be about time the government stopped this kind of illegality and put him on the school bench for a while. A shriek of laughter interrupted him.

German Harry in school, said Dante Louis, are you not quite clear in the skull? The schoolmaster is not yet born who can teach him anything. By the way, I want to see the captain, from the old country or the island sea, who can compete with Harry, as far as navigation is concerned. There is no such thing, despite all the papers and lessons learned. —I don't understand how he manages to get his ship out or into Brisbane, Sydney or other civilized ports, continued Smith, here any vagabond sailor can run in, even if he has no papers at all.

- It’s probably easiest if you ask him yourself, Ellison said. "I thank you," muttered Smith.

Otherwise, it's all very simple, Ellison continued, when German Harry, for example, is arriving to Sydney, he gets a captain on board who has a power of attorney and then he goes ashore and up to the harbor office and clears the schooner. When Harry is about to set off again, the same fellow gets them out, and when they get past Sydney Head the man is sent back ashore again in a dinghy brought for this purpose. Keine Hexerei, nur Behändigkeit, gentlemen. Cheers!

At midnight, while the three traders were still toasting and talking, the stillness of the lagoon was interrupted by an anchor chain, which rattled out from the hold of a ship. The three men rushed up, and the whiskey box on which Smith was sitting overturned right into the fire, where one of the black islanders was roasting a pig on a spit. Ellison stared out over the water.

- Mark my words! Do you see the tall stern mast - it's Harry anyway.

—The impudent devil, said Smith, saving his whiskey box from the flames, he doesn't care if it's night or day, he blasts away through reefs and surf, just as damned. One day he will end up in hell.

"German Harry always lands on his feet like cats," laughed Danty Louis. Authorities, customs and numerous others on three continents have tried to catch him, but he has always gotten away due to lack of evidence. He has always been as pious as a lamb. A nice lamb! repeated Smith.

However, Harry had made it ashore in a dinghy, rowed by two brown-skinned Tahitian boys. - Where there are decent people, more decent people come, he greeted the three and jumped ashore. And, look, there we have Smith. It's been a long time since we last met. A year and a half, I think. It's best if we manage our intermission at once, then I won't have to go around the South Seas after you. I have the bill on me, here it is.

Harry pulled a piece of paper out of his pocket and handed it to Smith. The interest rate can do the same, he said, winking with one eye at the other two. Smith, who was known to never pay his old debts, was caught off guard to the point where he ungrudgingly paid Harry the £50 as the others looked on in astonishment. Harry got a bite to eat, the others continued to drink.

- Well, what are you sailing with these days? Ellison asked Harry, his mouth full of roast pork.

- Copper, ivory nuts and a residual charge of dynamite, which I'm going into Lord Hove Island with on the way, Harry replied. - Is it shipping? asked Danty Louis.

- No, it's own cargo, said Harry, it pays better to sail with your own goods. - You haven't insured "Lizzie" have you? Danty asked Louis again. Harry laughed.

Since I have no license, it is not possible to insure the ship. But on the other hand, I save the premium. Big risk, big profit!

I never liked to sail with dynamite, Ellison remarked, I'd rather take the schooner full of savages from the Solomon Islands.

- Or wild animals, grunted Smith.

- Wild animals are not vices, Ellison replied, at least I've never heard of them. - I've both heard of that and witnessed it myself, said Harry dryly. He had finished eating and caught fire on his pipe. A load of dynamite should only be kept properly shelled under the hatches, and nothing will happen, but wild animals must be placed on the deck. They need fresh air, and that's where the danger lies. I can tell you a story about such a transport, if you care to hear it.

Harry took a deep drag on his pipe and looked out over the lagoon. It is several years ago, he began, we were on our way home with a full-rigger from Hamburg, had been to Japan and China and then ran into Saigon in Annam. There we took on board a whole menagerie, consisting of four Bengal tigers and a black satan, I think it was a panther. The captain was furious and explained to the agent that his ship was no zoo, but there was nothing to be done and so we must sail with the five beasts. We fed them during the trip, meat, bones, shark meat and squid. Once we put in for them a whole bunch of yellow peas left over from dinner, but they didn't want that kind of food, they just sniffed at it, hissed and looked angry.

- Actually, I wouldn't mind a plate of yellow peas right now, said Ellison, who was getting a little tipsy.

- Now shut up, interrupted Harry, and listen. We had two large cages on the upper deck just aft of the mainmast. In one cage we had placed three of the tigers and in the other the fourth tiger along with the panther. The two of them later sat staring at each other in their respective corners, and when, during the morning cleaning, we stuck the hose with which we flushed through the slats, they flew into a rage. The disaster came one day, after we had rounded Cap Horn and off La Plata entered a pampero.1 A huge wave swept in and smashed both cages. With a speed that would have made a Nova Scotia sailor pale with envy, the panther entered the gunwale, where it sat and drooled over the deck, while the tigers ran about and hissed on the bilges. A sailor named Otto had just rounded the galley with a tar broom and a pail of tar, when one of the beasts came rushing at him with gaping jaws. He was so frightened that he stuck the tar broom straight down the animal's throat, after which he fled for his life to the cook, who quickly closed the door behind him. From the valve window they could see the animal doing somersaults out on the deck, whereupon it tried to stick both front paws into its mouth at once. After two minutes there was not a single man left on deck except the helmsman, who dared not let go of the wheel for fear the ship would capsize. The lumberman was hardened when flayed alive, he stood inside his house with the door open, working on a spar without knowing what was going on, until a new wave washed one of the tigers right at him. The captain entered half-deck with a rifle in his hand to protect the helmsman, and from this place he succeeded in shooting the animals, one after another. We have to go up and get the panther down, after it was shot, it had become hanging with its claws entangled in the ropework. Well, was the lumberjack killed? Ellison asked, as Harry paused.

He hovered between life and death for many days. We had no other medicine on board than castor oil and the captain thought it was of little use. We then thought of giving him tar poultices on all the wounds and scratches, but of course it still became inflamed. However, the mate, whose name was Koenick, came up with a good idea, which I believe saved the poor man's life. We dissolved three braids of the best strong English tobacco in a tin can of hot water, then boiled the strong broth for two hours and gave him poultices with it. The mate believed that this strong sauce would kill all bacteria. When we were done with the bandages, the lumberman lay as if dead in our hands. The next day he began to roar as violently as the tigers, but eventually he was able to take in at least a bit of food. When, on 1South American term for a hurricane-like westerly storm. arrival at Hamburg, the doctor came on board to see the carpenter, who was now on his feet again, and was told what we had cured 102 him with, he only said: - God Father, save us! and shook his head. Since German Harry had sent the dinghy out to "Lizzie" later that night for more whiskey and a little tobacco, the conversation continued. Suddenly, Ellison asked Harry: What really happened to Captain Petersson, who you once told us about - he, who lost his entire crew in Santos?

- Yes, it was a sad and strange fate that befell him, said Harry and sat for a moment seriously thoughtful. So he told:

- It was, if I'm not mistaken, in 1878 during the great fever epidemic in Santos. Petersson had been lying inside the jetty with his barque ”Sydkorset" (Southern cross) and waiting for cargo for three weeks. Almost the entire city was depopulated. Everyone who could crawl or walk had fled to the mountains, where the air was cleaner. But then the crew on "Sydkorset" began to die, one after the other. Petersson alone did not catch the fever. A fortnight later he was left alone on the ship. All alone he buried the whole crew, sixteen men in all, and carried them on his shoulders up to the cemetery, one each day, and buried them all in a corner. On each grave he put a plaque with the name of the sailor and the ship and the year 1878.2 After much trouble, he later got a new crew sent to him from Rio, the worst jumbled scumbags on the planet, and then he sailed away.

Harry paused for a moment, the others waited in silence. The following year I was boatswain with Captain Petersson on the same ship. And I soon noticed that he was never sober. He drank everything he came across except sea water. In Rio, a doctor came on board and examined him. "That man has delirium tremens," he said to the mate. "He must not be alone in the room, you must assign a man to guard his berth at night, and of course he must not taste liquor of any kind".

The same day we sailed to Santos and the third mate was ordered to keep watch at night with the captain. Towards morning, when he thought the captain was asleep, he went in for tobacco and matches. When he returned a little later, the captain was lying in the bunk drinking from a bottle. The mate immediately saw that it was a bottle of brandy and it was emptied to the bottom before the mate managed to get it from him. Petersson dropped the bottle on the floor and fell back against the pillow. "It was good," he moaned, then died. Later we discovered that he had been upstairs and retrieved the bottle from a chest of drawers. Afterwards we found another one of the same kind. Captain Petersson was buried in the cemetery in Santos, not many steps from the sailors, whom he himself had buried the year before.

As the sun began to gild the palm tops on the beach, German Harry stood up and said goodbye to his comrades. The Tahitian men, who had slept in the boats, were already ready at the oars. Just as Harry was about to board, he pulled Smith aside, stuck him the 50 pounds and whispered, Just keep the money, Smith! We have had a nice night.

An hour later the schooner "Lizzie" appeared like a white seagull far out at sea. 2 In the cemetery in Santos, I myself have seen the sixteen crosses or canes with the year 1878 and the names, which, however, are partly illegible. Auth. - Harry is in any case a good sport, said Ellison.

- A most strange man, said Smith, it is not easy to fathom the depth of him.

- It is probably also best not to try, said Danty Louis. To which they toasted.

Chapter 8

Ted and the failed recruitment trip

German Harry's schooner "Galathea" went under full sail off the coast of the island of Malaita. It had been in a small practically unknown bay to recruit workers for the sugar plantations of Queensland. But the result had been completely negative, the blacks did not understand themselves well and did not understand how good it was on the plantations. They did not know the blessing of work.

German Harry had gone down into his cabin to get a little rest. When he awoke, he was surprised to see one of the crew, a young man named Ted, walking past his door with closed eyes and outstretched hands. Harry couldn't help but laugh. It was clear as day that Ted was sleepwalking. When Ted made it up the cabin stairs, a crash was heard. It was Ted, who tripped over something or other. Harry ran up to see what was on.

When he got on deck, he was greeted by a terrible sight. The "Galathea" had been attacked by the savages, who had come rowing in three canoes. The black, woolly-haired natives of the Solomon Islands were climbing like giant flies all over the deck and were already in a wild fight with the crew who were trying to throw them overboard again. Several of the blacks had already been killed. On the front deck a heated battle raged. Harry hurried aft and took over the steering wheel from the helmsman. It was important to get away now, before all the savages got on board and maybe even more made it to the scene. Harry offered a magnificent sight from where he stood. His upper body was naked to the waist, but on his head he wore, as usual, his large Stetson hat, which could hold three gallons. In the corner of his mouth he had a lighted cigar, which he chewed incessantly, and in his right hand a heavy caliber revolver. He should have been painted at this moment.

Suddenly Harry felt a searing pain in his head as if someone had burned him with a hot iron. He had to let go of the wheel and grabbed his head. His hands were full of blood, his eyes were dizzy, and the surroundings took on the appearance of a theater decoration. As if through a mist, he saw how Ted, with a face contorted with tears, swung an ax at the head of one of the natives. A bullet from the mate sent the black man overboard.

With a command, Harry called the entire crew aft. He then took out of a box at his feet a large cartridge of dynamite, lit the fuse with his cigar, and threw the cartridge toward the front deck. The effects were terrible. Heads and limbs were scattered everywhere. A couple of the savages just managed to jump overboard, but were eaten by the sharks. Harry sent off a fresh round of dynamite at one of the three canoes that were just docking at the rail, packed with warriors, who were swinging their spears and axes in a manner that left no room for misunderstanding. A few seconds later, nothing was left of the canoe, but black heads appeared everywhere in the water and the sharks were very busy again.

— Take care of the helm, Mac, said Harry to the mate, while I go down and get something to wrap my head with. I think they've had enough for this time, those devils.

A glance over the railing showed him that it was true. The two other canoes were on a wild flight towards land, while the savages who remained were in a hurry to fish up their comrades.

—I can't understand what's up with the blacks, Harry added as he went downstairs. They don't usually behave this crazy on this coast. It looks almost no better than that some fool has been inside and made a spectacle of them. They then always demand revenge on the first best white man. Now keep it well clear of the headland, Mac, the reef stretches far out in a southerly direction.

When Harry got down into the cabin, he noted with satisfaction that the skull was still intact. But he had received a big wound, and it pounded like a small thunderstorm in his head. In addition, he had annoyingly his nice Stetson hat spoiled. He had to keep an ugly scar on his skull for the rest of his life.

A moment later, when Harry came up on deck, the last traces of the clash had been cleared. Two of his sailors had passed into eternal rest, but the schooner was saved.

— Go away and get Ted! Harry said to one of the sailors. He lies away under the bow and licks his wounds, I guess.

A moment later the sailor returned with Ted. He had wrapped a strip from a shirt around one arm and was holding the cloth tightly with his fingers, but the blood was still pouring out in all directions and edges. Harry began to bandage his arm and then said:

— Now tell me, Ted, have you always walked in your sleep? "Yes, Captain," Ted replied, a little embarrassed, but I couldn't bring myself to bring it up as I signed on. I was ashamed of my weakness, and I think, by the way, that I would prefer to get ashore again at the first opportunity. Sea life is definitely not really suitable for me.

Harry laughed and gave him a friendly little push.

— You'll probably be allowed to come ashore when we reach Sydney, Ted. And I'm glad you woke me up in time, because otherwise there wouldn't have been a living soul on board by now. It was just a pity that I had to resort to the dynamite. I admit that it is the last resort I use.

As the mate and Harry later sat eating together on the aft deck, the mate said:

—I still don't understand how it all came about. Ted handled the ax brilliantly, I must say.

—Yes, Harry replied, he worked diligently. But had he not walked in his sleep and thereby awakened me, our heads would have graced the roofs of the canoe houses inside Malaita by now. It would have been a nice scandal!

Before I go on, let me tell you who Ted was and how he came to be patterned by Harry. Ted's story is not so common.

Ted hailed from Charters Towers in Queensland. He had come to New South Wales at a young age and been brought up on a farm near Wahroonga in the Blue Mountains. When one fine day he had grown tired of tending sheep on the farm, he resigned his post to, as he put it, take a look at civilization.

The first time Harry saw him was in Rawson's bar Kent Street. He was a tall, puppyish farm boy, who had pretty well greased lips as long as he had money in his pocket.

Before disposing of the last of the money which the farmer had paid him on his departure, one evening he bought a lottery ticket for the annual "Melbourne Cup" race and put it indifferently in his pocket. Some time later, after the horse races had taken place, one of the guests asked Ted whether he had checked whether the lottery ticket had come out with a win. Ted thought he had lost it and didn't care much about it, but he finally found it crumpled together with some old cigarette butts inside the lining of his jacket pocket.

The note was unfolded, and compared to a draw list. One corner was gone, but the number could still be read with some difficulty. All the guests jostled together to amuse themselves at his disappointment, for of course no one could imagine that he had won. Great was therefore the astonishment and jubilation when it appeared that Ted had won the top prize of £25,000 in the famous "Melbourne Cup". The host dropped a glass, which he was polishing, on the floor and wanted to see if it was real. Yes, the number was exactly right. Afterwards, Ted received unlimited credit in exchange for the host having the note in his custody, and Ted ordered champagne overall in Mrs. Fortuna's honor. Champagne, which was otherwise not an everyday drink in Rawson's bar, was obtained from a nearby liquor store.

German Harry and one of his good friends, Captain Carr, were just passing by on the street when they heard the commotion inside from the restaurant. They entered and saw every single guest sitting with a bottle of champagne in hand. Glass was not used. Ted was "a jolly good fellow" and ordered promptly a bottle of champagne to each of the new arrivals, after which he asked Harry if he wasn't a farmer, pointing to his pointy goatee.

"That's an insolent fool, then," thought Captain Carr, frowning.

"Well, maybe he's just a little inexperienced, the young man," Harry said. He's not even dry behind the ears.

Ted relived for eight days without a break, much to the benefit of Rawson's bar and to the delight of the guests, who had everything for free. The host, whose large, round face beamed with delight and satisfaction, had never believed that there were so many people in Sydney. The door of the bar was in constant motion, word of Ted's adventure had spread far and wide.

Finally the ticket was redeemed and the money arrived. Ted, now appearing in a large checkered gray suit, egg-yellow shoes, bright red tie and green hat, consulted the host and was persuaded to deposit the sum in the Sydney Government Savings bank, with the exception of a £500 line for current expenses. The host, of course, had already been reimbursed for his outlay. A clever journalist got an interview with Ted, a photographer took a picture of him in full war paint with a carnation in his buttonhole and a big cigar in the corner of his mouth, and then Ted went up into the mountains to impress the farmer. The farmer stared for a moment in silence at the phenomenon and then said:

Yes, Ted, you've been lucky, I can see, but once you've got rid of all your money one day, your old place is still open to you.

Ted gave the farmer a friendly pat on the shoulder and let out a laugh. In the small town, Ted settled down with a young widow, who owned the only tavern for miles around. The business didn't go so well, but thanks to Ted, better times came. The manager of the local bank office, who was a good friend of the widow's, often came and spent a pleasant evening in their company, giving Ted much sound financial advice as an expert. In that way, it gradually became clear to Ted that it was better to have the money transferred there, and the widow was of the same opinion. She thought it impractical for him to travel to Sydney every time he needed a few hundred pounds.

And so one day Ted appeared at the bank in Sydney, where he declared that he wanted to withdraw the entire sum. The bank clerk, who frowned when he heard the large amount mentioned, asked him to wait a moment. Ted was then politely asked to enter the director's private office. Here the director advised him of the imprudence of moving his fortune out of the safe bank vaults, etc., etc. Ted pointed out that he could very well manage his money himself, and mentioned that he intended to marry.

Well, good luck with the connection then, said the bank manager, following him to the door. You can withdraw your money after the usual notice. Of course, I cannot prevent you from moving the money.

Ted got his money deposited in Wahroonga's local bank, and all was well and good. The widow and Ted had agreed to marry, and never did the sun shine on such a happy couple until the day of the wedding. Then the bride and the bank manager disappeared over the mountains. There was nothing left of the big wedding dinner with subsequent ball, to which the whole town had been invited, and the flower-adorned church was empty.

The bank branch was closed and the pub was mortgaged up over the chimneys. For his last pennies, Ted made his way down to Sydney and drowned his sorrows in Rawson's bar in Kenth Street. Here Harry found him exactly two months after their first meeting, poor as a church rat. When Harry asked him if he wasn't sorry to have lost all his money, Ted stoically replied that money was only a nuisance.

Harry ordered two glasses of beer and asked Ted what he was going to do next. — Ideally, I want to travel far away, Ted replied. If I knew any captain who had use for me, I would gladly leave tomorrow.

Harry said he probably knew a captain who could use a man, so if Ted wanted, it could perhaps be arranged immediately. Yes, but you are farmers, right? asked Ted.

Yeah, but that doesn't mean anything, it'll sort itself out anyway, said Harry. The following evening, Captain Carr came into the bar and met Ted. He offered a glass of beer and said he came from a captain to pick him up. He was to be a midshipman on a schooner, which was going out to the islands to pick up a cargo of copper for Sydney. They left the bar, and along the way Carr described the glorious marine life with such warmth that Ted was about to fall over his own legs in his eagerness to get away.

In Darling Harbour, Carr spied a schooner, which was anchored some distance out, and a moment later Ted saw a boat come in towards the wharf, rowed by two black Santa Cruz sailors. These were, on account of their coming to a big city, dressed in "party clothes", i.e. swimming trunks, a stick through the nose and the eternal chalk pipe stuck through one ear. Ted stared at them in disbelief, but Carr helped him into the boat. Once on board, Ted was led by Carr down into the dark, gloomy stockade, where he was assigned a berth among ten black cannibals. After that, Carr disappeared. When Ted came on deck the next morning, German Harry stood smiling and received him. Ted rubbed his eyes and didn't understand a damn thing.

So began the journey, about whose dramatic events I have already told before. On the schooner's return to Sydney, Ted said goodbye to German Harry, and shortly afterwards he regained his place with the farmer at Wahroonga. In the meantime, he had learned a little bit more about life.

Chapter 9

Wrecking of "Quetta"

Everything I have told you so far about Harry I have from his notes, from what others have told me about him, and from what he himself told me, when we were together and he let his thoughts drift back to old, stormy times. Now I want to turn to telling what I myself experienced together with him during the four years I knew him and traveled with him, from 1910 to 1914.

It was good times in Sydney at the time, when I became acquainted with Harry. One day, some time after I had followed him to Middleton Reef, I came strolling down King Street. At least half a dozen times I was molested by people who asked if I wanted work. But I had about a pound of silver in my pocket, and could afford to say no.